Those Fifteen Seconds

The other day I was watching an old Tamil cinema on cable television, along with a friend of mine for whom any movie produced after 1965 is no movie at all. This film had a robust and cheerful heroine who, to borrow my grandmother’s words, was ‘looking well-fed and happy like a calf in the palace’, which in the common parlance would mean being a tad obese. The lady, through a judicious application of her histrionics was a scene stealer in her heyday when she reigned as the undisputed queen of the tinsel empire. She was intimidatingly filling up the screen space on my television while on tight close-ups, was hogging it considerably at mid long shots edging out others and moved as a considerable mass of black and white as the camera pulled out in long shots, as the story unfolded.

The movie was half way through and there was this enchanting scene of her dancing with abandon on the embankment of a huge reservoir and then climbing down the steps of the massive concrete barrage pretty fast for her girth, lip synchronising all the while a medium paced song extolling the virtue of the Indian women.

‘Awesome; what a ravishing beauty she is’, my friend was screaming in ecstasy as he sat glued to the TV. I grunted in agreement munching a fistful of popcorn from a huge plastic bowl and watching the damsel dancing on the dam. My stare was fixed more intently on a specific region of her anatomy, namely her ample arms covered inadequately by the shortest sleeved pink blouse with an enchanting lace work, she wore.

However, I was not into a silent celebration of the human female body but was only glaring at the two near circular scars, rather marks the size of an one rupee coin on the screen heroine’s left arm, immediately below where the short sleeve of her blouse ended. I sat fascinated by those vaccination marks indelibly etched on the supple flesh of the lady with a radiant smile.

They were the representative socialist beauty marks adorning almost every arm, from the Beauty Queen to the municipal conservancy worker, the landlord to the landless, the wandering ascetic to the small trader, the industrial magnate to the factory worker, throughout the the country, half a century ago.

If you think vaccinating is a hackneyed humdrum job, there you are veering away, ninety degrees off at wrong. I vividly remember the vaccination camps I have had witnessed and participated in the sensational sixties as a primary school student and can emphatically say that like every good job, it comes with its own rhyme, rhythm and reason.

It all would start with a fatigued four-wheel drive jeep with the oblong Government emblem drawn on the flanks and at the back, strenuously inching through the potholed road that has not seen a decent coat of bitumen for ages. The vehicle would be coming towards our small town, quite early in the morning.

As it would approach the milestone at the municipality limits, the jeep mysteriously would develop a technical snag, grinding to a laboured halt, moaning in distress. The local elders with tucked up dhotis partially covering their loosened and dangling loin cloth and with a long thick lighted Trichi cigar precariously held on their lips would be walking briskly, patting themselves loud on their posterior with an intention of aiding and abetting a smooth session of answering their call of nature at the largest open air toilet under the sky. They would be the first few to observe the arrival of the vaccinators and would help giving the jeep a collective push forward in an attempt to revive the engine.

A few youngsters hanging around would also volunteer to participate in the proceedings at that stage. This inquisitive lot would often look thoroughly into the jeep with probing eyes and would take a few mental pictures of the men and the material within. They would then run towards the dwellings, informing no one in particular in loud voices, ‘The vaccinators have arrived’.

For a few minutes then on, it would be all hell broke loose. The turmoil would be grossly equivalent to, if not more than that was known to be created by the German war ship Emden that bombarded Madras during the First World War.

Everything would ground to a halt in a few houses in every street with the families immediately locking out the premises and taking the next available train or bus to their close relatives’ place, a minimum 50 kilometres safely away from the port of departure, with a prayer on their lips that the vaccination menace would not have spread to those distant lands.

The jeep would emit a thick jet of black, odorous vapour with the engine revived. It would move forward slowly and would be pulling up puffing and panting at the kerb of our street.

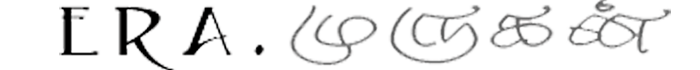

The vehicle, in all probability would be the one coming from the Primary Health Centre at the nearby district headquarters. Along with the emblem, the name of the Government department in Hindi would be prominently visible on the sides but no one gathered there including those riding the jeep would be able to read it, ours being a landmass where Hindi is an alien language.

The four or five Government servants who arrived at the scene would alight from the jeep without losing time like firemen at the site of the inferno and would run forthwith into the almost deserted streets. They were normally referred to as NGOs, a term not to be confused with foreign aid agencies but only meaning Non Gazetted officials which further would be interpreted as those not finding their names on the Government notification announcing the names of their officers.

A few other families might be of the same mind-set as of the refugees mentioned before, but with something to peg them to their homes like having elderly family members who would not undertake a travel or the running of private lines of business like oil crushing and mongering or tailoring or maintaining a poultry farm or rearing studs to impregnate the cows for a fee. That would render any thought of immediate check out impossible. They would then settle for their Plan B to face the risk, yet, significantly minimizing the ‘damage’ done.

Thus they would restrict their regular movement outside their dwellings and would keep the doors closed throughout the day, becoming nocturnal owls for all practical purposes. In case they would get vaccinated, to render that ineffective, as it would tantamount to revolting against Gods to ward off smallpox and measles which are God sent, with vaccination, they would quickly prepare a ferocious mixture of cow dung, furnace ash and a few other exotic elements like neem seeds, soot from the oil lamps, dried ginger and turmeric. Such a concoction would drive away all vaccination triggered evils, they firmly believed. Needless to say, this ammunition would be prepared in sufficient quantities and kept ready in their backyards, under diligent care.

To make them see reason and to understand the importance of vaccination for public health and the urgent need to eradicate smallpox from the face of the Earth, the school teachers would immediately form a self motivated brigade and would start visiting households one by one with their rational and educative narratives and with humble requests to one and all to get vaccinated. Some of them would visit the bus stand and the rail station to bring back the escapees before they board their train or bus.

These school masters would be enthusiastically aided and abetted by their young students, all functioning together with a missionary zeal.

The vaccination inspector would jump out of the jeep and would start walking as if he is moving on the moon’s surface. He would throw a quick glance at the houses in the street with apparent disdain and would smile a little at no one in particular.

By then, two chairs would have arrived at the scene from the panchayat board president’s house. These wooden chairs would have been fetched from their place of origin, along with a million bed bugs those being the permanent residents of the aging wooden furniture. The chairs would be deposited at a corner off the street near a tree if the street has a few shady trees or right on the kerb.

Moving sideways quite often and up and down as if sitting on a spring cushioned sofa, to defend himself from the ever hungry bed begs hidden snugly at the numerous crevices in his chair, the vaccination inspector would retrieve a file with red flaps and would keep the page open for the names of the residents in the street who are eligible for public health initiatives.

The jeep driver and a couple of orderlies from the visiting party would knock at each door and invite the residents to the grand ceremony, repeating at each household, ‘Our respected officer sir has arrived and is waiting to meet you.

Please come with family’.

Another orderly would be lighting a kerosene wig stove with insufficient oil resulting in a thick smoke and an unbearable stench rising in the air. The vaccination inspector would order his men to procure the necessary supply of fuel forthwith from wherever it is available at no cost.

After running like headless chicken, they ultimately would return from the Panchayat President’s house with a green bottle full of kerosene and with a handful of coconut strands sealing its mouth in place of the missing stopper.

By then the anti-vaccinationists would have realised it would be futile to offer resistance to the mighty first line foes from the Government and the still more formidable second line, of the teachers and students. They, with calculated indifference would make themselves available for undergoing the indignity of getting vaccinated.

An aluminium utensil with a broad base like the one used for cooking rice for marriage feasts would be placed, half filled with pond water atop the stove. As the water gets heated, a few metallic contraptions like wheel and axle arrangements for miniature trucks bristling with sharp round teeth would be casually thrown into the boiling water for making them sanitized.

The students would look at these instruments of torture with lurking fear and would gaze in the direction of the teachers who with a broad smile would provide the necessary solace and confidence, telepathically. These teachers would also set an example to their disciples and other townsfolk by offering to get vaccinated first.

Sometimes, there would be a lady vaccinating inspector for providing services exclusively to the womenfolk and if specifically requested, for children too. The lady inspector would feel out of place anywhere and as the vaccination festivities proceed with gusto, she would sit in a corner trying to read the previous day’s newspaper repeatedly, waiting for the womenfolk to arrive.

Praying from the heart for the ordeal to be over as soon as possible and with eyes partially shut, we would stretch the left arm to the vaccination inspector. He would wipe a swab of cotton wet with some hospital-smelling preparation like tincture of iodine and would pull the extended hand up a little so that it is kept straight at the arms, in readiness for the main ritual.

A hot wheel of metallic teeth would now rest firmly on the arm and would rotate digging deep into the flesh bringing tears to the half shut eyes and a pathetic moan in agony in some. The tooth wheel will perform an encore on the tender flesh a little below the place of the previous attack giving rise to all pain that could be induced within fifteen seconds. The officer would smile satisfied at his work and would dismiss the youngster forthwith, ordering the next eligible candidate to occupy the wooden stool.

To think of it now.. if not for the fifteen second pain, I would not have been sitting snug and comfortable watching the old movie of my choice and writing this. Nor would there be the fleshy heroine with prominent vaccination marks on her shoulders like those on mine or those on the valiant hero’s arms or those of any other member of the movie cast and crew or the past-the-prime audience. We all would have encountered an inglorious death long back in an epidemic of smallpox or would have lost our eye sight or would have become permanently disfigured.

I look with affection at the scars of vaccination on my left arm that came up there fifty years ago and thank the perpetuators of the fifteen second agony. You gave me a new lease of life, free from smallpox.